Spirit on Ground

"I never seek to make what they call a pure or abstract form.

Pureness, simplicity is never in my mind;

to arrive at the real sense of things is the one aim." Constantin Brancusi

"I was looking at a grain of rice. I was about to cook it. I realized that I was hungry and if I ate the rice, I was going to continue to live and think. So it had this human potential. If I would throw it in the garden, it would have growing potential. It would know how to grow into more rice because of its genetics. So I looked at the rice and it looked like a piece of alabaster, it did not look like a barcode or a double helix. I looked at it closer and closer and it looked just like stone. I was really amazed at this crystal that looked like stone. It was hard as stone, it looked like stone and it knew how to grow into rice, knew how to grow into human thought. So it was a contraction of potential and therefore it must know its entire past, my past and its past. Somehow that rice went into the beginning of time and matter and form. As matter it does, because we know that things keep changing; over time they wear out, fall down into particles and through creation and pressure things are build up again. And somehow there was mind, there was something going on in that grain of rice. This made me realize that the present is an accumulation of the entire past. The past unfolds in the present. So the past is not something that is gone. The present is the past. (...) That makes sense to me." (John Greer)59

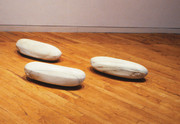

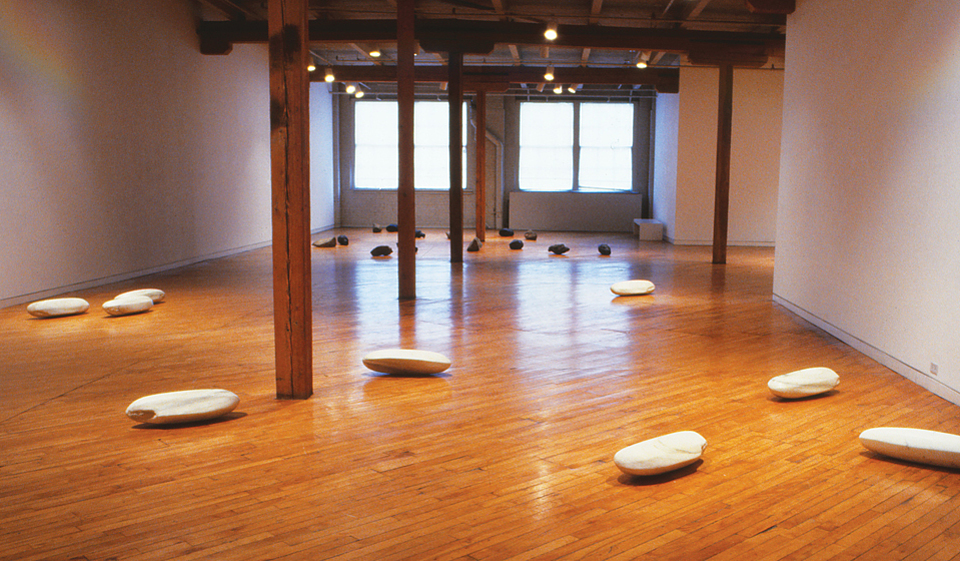

"9 Grains of Rice" 1991 is a work that is composed of nine pieces of carved carrara marble in the shape of rice grains. They are positioned directly on the floor, seemingly arbitrary. In fact, the artist uses real grains of rice as models, throwing them on a sheet of paper in order to determine the position of his sculpture in a natural dynamic inside of a given space. The reduced and contained shape of the forms are irritating at the first glance, since they do look familiar, but in the presented scale they take on a different formal dynamic. They make us develop self-consciousness as walking objects between resting objects. This state of rest is not that of immobility - as they seem to be floating right above the ground. They do look like extracts from somewhere else added to a plain floor surface. Once identified as grains of rice, they reflect on our scale, diminish the human uprightness and pose the question of a relative importance of "being" and object.

The whiteness of the material and the denial of weight, through the dynamic in the reduced shape, establish a spiritual atmosphere among that work. The sense of space and time that is captured in this work is very close to an understanding of space by Isamu Noguchi: "The essence of sculpture is for me the perception of space, the continuum of our existence. All dimensions are but measures of it, as in relative perspective of our vision lay volume, line, point, giving shape, distance, proportion. Movement, light, and time itself are also qualities of space. Space is otherwise inconceivable. These are the essence of sculpture and as our concepts of them change, so must our sculpture change.

Since our experience of space are, however, limited to momentary segments of time, growth must be the core of existence. We are reborn, and so in art as in nature there is growth, by which I mean change attuned to the living. Thus growth can only be new, for awareness is the ever-changing adjustment of the human psyche to chaos. If I say that growth is the constant transfusion of human meaning into the encroaching void, then how great is our need today when our knowledge of the universe has filled space with energy, driving us toward a greater chaos and new equilibriums. I say it is the sculptor who orders and animates space, gives it meaning. (Isamu Noguchi)60

With the "9 Grains of Rice", Greer tries to capture exactly the described notion of time and space as correlating continuum. Rice is a materialized potential, it includes natural determination to serve as part of a food chain for living organisms. The essential factor for Greer is that rice is human mental potential. The material is on the crossroad between those two forms of existence. So again, he expresses his take of time through a metaphor that makes sense to him, yet does not leave any doubt about the complexity of the interrelation of time and space. "In a manner of speaking, space is an intermediate zone between the cosmos and chaos. Taken as the realm of all that is possible, it is chaotic; regarded as the region in which all forms and structures have their existence, it is cosmic. Space soon came to be associated with time, and this association proved one of the ways of coming to grips with the recalcitrant nature of space." (Dictionary of Symbols)

Greer’s understanding of this phenomenon is guided by a belief in the complexity of matter as form of memory, of accumulated history in form. It functions as door to an infinite past, which in turn defines the positioning of matter in regard to what we call future. For Greer "history" is most subjective, and memory is objective. His definition is developed out of the understanding of memory as something physical, a physical presence of a collected past. This understanding expresses his turn towards the substantial material of stone as a medium for art objects. He tries to establish a relation between our physical existence to what he wants to visualize in his making of art. "Art expresses, it does not state, it is concerned with existences in their perceived qualities, not with conceptions symbolized in terms. A social relation is an affair of affections and obligations, of intercourse, of generation, influence and mutual modification. It is in this sense that "relation" is to be understood when used to define form in art". (John Dewey)61

Greer is using natural forms in his work. It is important to realize that he is using images in a representational way, not a pictorial way. Representational does not mean he is representing a grain of rice. Moreover he is taking the shape of the grain in order to represent a nature of form, he is defining a relation. Every matter and material has its form and we establish through that a system of recognition. Yet behind this individuality is a general condition that contains an essence of formal "rightness". The true experience of an object takes place through visual, tactile and referential (through mind) perception of an object. Greer tries to define this essential act of experience through the use of images. As much as he sees the problematic in traditional materials as an advantage, he is tackling the problem of depiction as such. He is transforming imagery into sculpture - and is transforming the viewer into a perceptive and engaging counterpart. Thus we perceive stone as form of something, as form relating to specific experiences on a quite different level of associations. This encounter, which helps to clear the senses for the essence of form, allows for various personal interpretations.

The "Grains of Rice" are not without any surface detail. In fact they even show a rough broken part at one of the ends, in analogy to the part of a grain of rice that leaves traces of its source. Once again we find the "broken-edge" as an indicator for a continuum.

The essential quality of a reduced and pointed formal canon reminiscent of natural forms of disorder (not applying a systematic scheme) is a concern with a long tradition in visual articulation. I am discussing two examples, "The beginning of the world", 1920 by Brancusi and a "Head of a canonical figure" from the Keros-Syros culture, an antique cycladic work. In connection to this specific work it becomes obvious that they were true inspirations for Greer.

In his egg-shapes, Brancusi is not working towards "simplicity", since the egg - and especially the forms that Brancusi carved - is not a geometrical shape. It is extremely simple, but it is as well extreme in the sense of not being measurable. "The "simple" of Brancusi is the extreme opposite of the explicitness of the geometric-axiomatic. "Simplicity" is not an end in art, but an inevitable approach to the real sense of things." Brancusi states. Brancusi's simplicity stresses the indispensability of things, which comprises the condition of being non-constructible. Constructible, repeatable are the objects of a scientist and industry, not the objects that are part of our life." (Dieter Rahn)62

According to quotations of Brancusi, he saw the idea behind the objects as their essential existence and, in this aspect, is considered close to Plato's ideas of sculpture as harmonious and ideal forms that are beyond anything accidental or irregular. In fact, Plato’s distinction of an outer form of things and their deeper significance in the essence is not at all a point of consideration in Brancusi's work. For Plato, asymmetrical and irregular elements in a work of art would be part of the realm of diversity and thus refer to the world of the mere reflection (Schein). "Brancusi's sculptures do not repress the irregularities of destiny and the deviation of life, the lack of symmetry of existence, that would obscure such a unity. They bring them up in their elementary structures. In Brancusi's simplicity, diversity is not a fictitious world that has to be overcome. It gives life to simplicity. It is exactly the earthy earthliness in its imperviousness that is realized by the rhythm of the plastic figure and the architecture of the base." (Dieter Rahn)63

In this sense it is wrong to define Greer's approach to art as art as mimesis - because his work is not about a depiction of an object. It is about the infinite qualities of life - in its binary qualities of idea versus matter, which can be experienced through form in matter. For Greer, matter or material is not a raw material for production at hand of a fictitious idea of progress and "human creation". Material for him is contained memory that he tries to release into a breathing of life through the experience during the act of art.

Turning towards the "Head of a canonical figure" (Keros-Syros culture, marble, 9 13/16" high), an example of early Cycladic art, it is noteworthy to state Greer’s admiration of these works, which he appreciates even more as they were not meant to be seen as art. "If we contemplate the large Cycladic head in the Goulandris Collection, we may gradually come to feel what is for us a major achievement, a very considerable work of art. The simplicity of the form does not become trite as we look, nor do the elements separate themselves in such a way that they might adequately be described in words and so dismissed. The qualities appear to us to be immanent ones, residing tranquilly and within authority within the marble." (...) "Turning again to our Cycladic head in the light of the issues of abstraction and representation, we see that it is indeed reduced to essentials. But these essentials are not simple geometrically definable forms: spheres, ellipsoids, or cylinders. There is nothing parthenogenetic about the way the forms arrived at." (...) "Cycladic sculpture thus offers (...) a whole range of consummately accomplished solutions of the perennial problem of the sculptor, the representation of the human head in a manner that uses form rather than surface detail to impart vitality and dignity." (Colin Renfrew)64

Greer is taking up on this dignity and vitality when he is using images as metaphors. To grasp the essence of vitality does not mean for Greer to reduce the tactile qualities of the object. His medium is the object and so he uses details of form and surface in order to reach the viewer in a language that is understandable through object qualities that are referential to our life. These formal elements are not images, but - and that is important in connection to his scaling of objects - they are essential as what they are, form in stone which is attaining a new substantial encounter in relation to a person. His use of symbols - as I already started to explain in the chapter "WElcoME" - has a ready-made quality in the Duchampian sense. Greer uses his imagery in order to give the viewer access to an essential quality of the encounter of an art object. Herbert Read refers to vitalism in connection to Brancusi as the pioneer of the universal element of spirituality in modern sculpture and to several modern sculptors, like Picasso and Moore: "He (Picasso) is concerned to represent in his figures certain vital forces of social significance - the anima that we project into all subjects, animate or in-animate, the quality the Chinese call ch'i, the universal force that flows through all things, and which the artist must transmit to his creations if they are to affect other people. This vitalism as I prefer to call it, has been the desire and pursuit of one main type of modern sculptor." (Herbert Read)65

Greer does not only want to capture a vital quality in his sculpture, but through the positioning of the objects and the imagery that he uses, he is defining the experience of an art object as a meaningful encounter, a vital experience. Mimesis is a means of language for him in order to merge the aura of art with the essence of experienced life.

A very fine example in succession of the discussed approach is the "Wasp Nest", 1993. It is executed in white marble, approximately 80cm in height, in the shape of a wasp nest. The activity of swarming insects is grasped in the oval form that is transforming its dynamic through a spiraling surface. The white marble seems to dissolve, in spite of its substantiality of material, into a continuum and at the same time becomes a container, because it is a hollow object. The opening on the top is a polished "navel hole" - the scale again is in direct relation to a human body. The suggested movement and activity of flight is responding to human aspiration to overcome immobility and gravity. The work is explaining a similar spiritual state and is talking through its form and tactile qualities.

"Rose of Verona Rose" 1993 is another example of object qualities that contain energy potential in reference to an unfolding of life in a natural form, a rose. Red marble with rich veining is signifying living colour, warmth of blood in stone, flesh imposed on a plant out of stone. The potential is the same that is reining the empowered plant before blossom. The size is provoking the quality of eternal spring, the power of growth coming in an outburst of natural life over the sleep of winter.

Roses become a metaphor for Greer to define an earth-connection - opposed to the spiritual inclinations of the grains of rice.

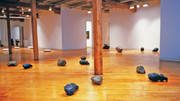

"7 Rosebuds in Iceland" 1994 consists of 14 elements, "7 pieces manufactured and 7 pieces extracted from the land." (Greer). The manufactured components are in the form of tightly closed rosebuds, roughly the size of human heads. They are all cast from one mold, patinated a deep, dark blue, that appears to be slightly frosted. An equal number of found, almost black volcanic crystals are shown together with the rosebuds. "Part of my thinking regarding this work is the flow of molten metal and the flow of the molten rock. The magma rock from the heart of the earth - from the molten core. The cooling of the rock gives the land its natural form. The cooling of the flow of the molten metal in the mold defines the cultural/manufactured shape of the rose, the rose being a plant of high cultivation for thousands of years. The solidity and density of the rock. The hollowness and the resonance of the bronze. The application of the acid on the flame heated metal giving the colour of the cool deep night sky. The volcanic tempered in the ice and snow. The hot and cold in the light and dark. The cold salt Atlantic lapping on the volcanic stone. The memory of fire, passion in a rich, harsh environment. Flowers scattered amongst the harsh, bare rocks. Internalized potential, including the fragile sensuality, implied in the image. Human presence on ancient land. (John Greer)66

It becomes evident that the chosen material is significant to the subject matter of the work. The qualities of the bronze are compared with the qualities of magma rock - both resulting in a shape that seems to refer to each other. Each rosebud is visually paired in the installation with a magma rock. Because of the density of the colour and the contained energy of the forms, one is literally grounded by walking among the objects.

This work is defining the viewer as a cultural object. We re-examine our position not only in connection to the object, but become aware of a human encounter among natural conditions. Our sense of scaling is increasing the scale of recognized subjects - thus is psychologically adjusting the viewer's significance to nature. Greer describes this re-definition of our relation to the world as being of the world. The darkness of the colour, the harshness of the forms, the density of the rock in connection to the delicate tenseness of a rosebud visualize the extremes that civilization is facing: the most harsh conditions like coldness, roughness and times without day and sun. It is almost a melancholic piece that is not talking about death, but about the richness of life, a potential of the force of growth, about an energy that inhabits cultural civilizations in the face of raw natural forces. Here, the rose is a metaphor of culture imposed on nature and enters in a dialogue to true natural forms. Nobuo Sekine, a contemporary Japanese sculptor described the initiation for a sculptor's activity in a sense that is very close to Greer's and is interesting in connection to this work: "There are times when we see things (as) clearly as if they were enveloped in a magnetic force. A new, fresh encounter with plain ordinary things that are just lying about in reality. It is only for a brief moment, and it is only a personal experience, but at that time we think to sustain the perfection of the encounter and make it universal. (...) But this process is definitely not "creating". It is rather sweeping away the conceptual dust that gathers on the surface of things, then turning them into what they really are and presenting clearly the world contained within them. Making visible that which can not be seen. And it is not separating them out, defining them and then carrying out the details of their construction. Rather, it is strengthening their presence. Like flowers brought in from the field. Flower arranging is definitely not a tool for asserting one's ego. But rather giving to flowers themselves a new life. (Nobuo Sekine)67 With this statement Sekine captures the understanding that Greer is following in the reception of a person as cultural object in reflection on nature.

Another work deals with the culture-nature aspect quite deliberately from the opposite point of view. With "Thorns", 1993 Greer is forming a statement of nature into three bronze objects. The objects are formed in the shape of rose thorns, stripped from a twig, but still holding some remains of the bark. The patina is dark brown on the bottom dissolving into a bright yellow at the end of the tips that are pointing in continuance of a slight curve into the sky. The extracted forms contain a threatening element, standing in opposition to the viewer like guardians on duty in a height reaching app. 80 cm above ground. We could see them as a metaphor for human intervention into nature, of a constructed nature that fits in the cultural context. With these objects, yet, we suddenly face the other side. This encounter is again shifting the scales and so redefining a dignity of matter in respect to the earth. Greer's thorns are collected and arranged for a re-scaling of a human encounter of the world.

59 John Greer in an interview with the author, Berlin, March 1997

60 Isamu Noguchi, Dorothy C. Miller, Fourteen Americans,

New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1964, p.39

quoted in Eduard Trier, Bildhauertheorien im 20. Jahrhundert,

Gebr. Mann Verlag Berlin, 1992 Neuauflage, p.106

61 John Dewey, Art as Experience, Perigee Books,

New York, 1934 c, 1980, p.134

62 Dieter Rahn, Die Plastik und die Dinge,

Rombach Verlag Freiburg 1993, p.244f.

63 Dieter Rahn, ibid.

64 Colin Renfrew, The Cycladic Spirit, Thames and Hudson, 1991, p.176, 180

65 Herbert Read, Modern Sculpture, A concise History,

Thames and Hudson, 1964, pp.76

66 John Greer in a statement on the work "7 Rosebuds in Iceland", 1994

67 Nobuo Sekine, "Activities 1968" in Makoto Ueda, ed. 1968-78,

Tokyo:Julia Pempel Atelier, 1978, quoted in Janet Koplos,

Contemporary Japanese Sculpture,

Abbeville Modern Art Movements, New York, London,

Paris, 1991, p.73