Waiting in Silence

A stone is that from which we come,

is that to which we go back, it's the earth itself.

Isamu Noguchi

As explained in connection to John Greer's use of symbolism in combination with a substantial material like stone, it becomes evident that he applies significant importance to the work of art in its role as a form of memory - memory in form. This definition does not correspond with what we might connect to a memorial or a monument, since it is working on a fundamental level - which in turn defines the function of art as memory in general. Memory is not a measurable figure or a stable or constant entity in space. It gains form through human interaction - through human intervention in the world of matter.

The beginning of what we call art is going hand in hand with the beginning of man forming his own world. This world of phenomenology was in the beginning very close to the essence of life in its physical existence. The occurrence of art is defined by the need to illustrate and give form to personal experience. It is a direct translation of mind into matter, provoking a mental response through and with the material world. Dennis Vialou writes in "Frühzeit des Menschen” / "The early days of mankind": "Prehistoric art is not a narrative of lived life. Life is in the core of its images of animals or humans. It is its very basis, takes on a pre-eminence which helps to overcome the anecdotal, the common and its death." (Dennis Vialou)87. He looks for the origins of art, which are one with life in the "mysterious bowels of earth". In fact, what we know about prehistoric cultures, is only through objects and cave drawings which we found - articulations from times that are beyond written documentation, but reveal more about the inner truth of our immanent ancestry than anything that follows a pattern of symbols that has to be decoded through a system, a mental construct. Vialou concludes his investigation of cultural production by ancient folks: "Even if the cultural memory is forgetful, the remaining prehistorical forms visually capture the memories of the former human beings. These forms took over their shapes, because the beauty of the models merged harmoniously with what the artist's vision considered to be beautiful. Realized conception on the one hand, objects and landscapes on the other hand, thus formed an entity. The long dialogue between envisioned forms and materials from bone and stone has produced works of art which came to life by the breath of nature." (Dennis Vialou)88.

Vialou regards ancient artifacts as the beginning of art, because of the element of the beautiful. Even though for most objects the exact purpose remains hidden behind suggestions and doubts, it is certain that they served more than the purpose of function of daily use. They had a meaning that was beyond a mere functionality as crafted objects. Ideas are placed in the real world and the factor of time is still nourishing the dialogue between man and nature, man thinking in nature, man defining culture, man in harmony with nature, man in opposition to nature.

The following two works of John Greer are talking about a presence beyond our world, about a different sphere of REALITY. Here, Greer is talking about culture and its diversity and expresses his interest in a dialogue between the memory of different ancient cultures and us, as human objects among them.

In "Vortiginous", 1994 we find ourselves as witnesses of the continuing involvement of man in natural dynamics, the flow of air, movement and sound. Vortiginous consists of three figures carved in marble, two of them worked after hand-sized artifacts from prehistoric times, but appear in his sculpture "life-size" in relation to the viewers' body. The walrus man is a standing figure that seems to be half way in between man, because of the body, and walrus, the head of this figure. The large and heavy head with long ivory teeth reaching up to the waist, is lifted slightly up, suggesting an awareness of the surrounding. The arms are folded across the belly, which is exposing a huge hole running from front to back. In contrast to the surface of the figure, which seems to be covered with fur and is fairly rough, the inside of the "mystic hole" is highly polished. The second figure is a flute player, which is reduced in its features and does not bear too much surface detail. The hands are lifted up in order to bring two pipes to the mouth. The head is lifted slightly upwards, suggesting a sound flying out into the world.

The "walrus-man" is originally an artifact that is made from ivory and only 7cm/2.75” in height. It is dated to the Late Thule Tradition and was found at Point Barrow, Alaska around the turn of the century.89 It combines human and animal features in a refined carving. Right through the belly of the figure goes the aforementioned "mystic hole" and it is not known which purpose the figure with the hole served. The second "original" artifact that Greer used as reference is a prehistoric "flute-player" from the Cycladic Islands. It is dated to the Keros-Syros culture and is executed in marble in a height of 20cm/7 7/8"90 This figurine includes a tranquil movement, the rhythm of the flutes that give a vital element to the unknown original purpose of the work.

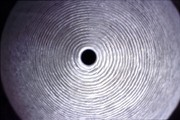

Greer used these artifacts in the same way, as he is using imagery with a ready-made quality. He uses them because of their quality as memory in form of a fetish, which includes a very personal intimacy of the beholder. Greer translates this quality into sculpture made of stone, uses a scale that puts the figures as opposing objects, man-made things into our way. He himself describes his scaling as "critical". He scales all his sculpture "according to my arms reaching from my body. I like hugging things, I like picking things up, I like things holding me down, I like climbing over things, so all the physical scales, the physical associations and this physical kind of reality is critical in the work. It would not mean anything to me, if you could not engage with the work that way." (John Greer)91 This aspect of physicality is stressing Greer's search for the essence of reality. He adds a third element to the two "life-size" figures: a wasp nest carved in stone. It is about 80cm high and has a dynamic surface, spiraling around the form up to the top hole, which is big enough to reach inside with a finger. The marble wasp nest is hollow and the inside surface of the hole is smooth and highly polished. Through an upscaling according to the importance that is defined by the artist, he is translating the qualities of movement into a form of experienced encounter. This third element is actually a way of including the viewer in the work through a movement that might best be described as a “following”. It is a receptive following as well as an active and conscious engagement. Essential to the work is the “unknown”. It is an unknown origin of the imagery and object quality of the figures, reflecting on the unknown element of experience among them. Through the imagery of the sculptures and the vital aspect of the dynamic, we are included in a movement that is established between object - image - idea - and the reality of now: it is the element of activity through “sound”. Sound is rich in associations and therefore a creative experience. It is combining natural and human forces - and set free by the act of consciously responding. In "Vortiginous" there is a combination of the silence of the pipes, the sound of the mystic hole in the belly and the spiraling and upwards movement suggested by the wasp nest. The complexity of the movement is reflecting on a vortex as a strong implication among the sculptures.

In this work history is refused with the elimination of the distance of time - and through that, it is placing the work and us into the objectivity of evolution as form and intelligence.

Through tactile detail the artist enriches the work, like polished versus rough areas of stone, holes and full forms that are responding to the body while one is investigating the work. Greer has a profound sense of stone as a material that discerns a fundamental experience of life. Carving stone puts him close to the essence of an experience of truth in nature, man being part of it. The force of gravity, and through stone, the centering of existence, translated by him into sculpture, is, what shows him as a person that is conscious of presence and past, linked through the self as a being that is expressing thought in sculptural form. He himself imposed a difficult task on his work that is combining honesty to material with an imagery that is sincere on a basic timeless and a diverse contemporary level.

"I learned a lot from that rock rolling down the hill. It is talking about the transitional balance and I like the idea of that. I talk a lot about 'everything changes, but something still remains' (which was a subtitle of a traveling show in 1981). When I talk about the transitional balance, I think of that stillness. I think a lot of art tries to get to that stillness. Balance in the universe, a quiet rightness. That is an important thing. That is mostly what my later work is trying to get at."92 This personal claim puts him close to the idea of the sculptor Isamu Noguchi, who wrote: "New concepts of the physical world and of psychology may give insights into knowledge, but the visible world, in human terms is more than scientific truths. It enters our consciousness as emotion as well as knowledge; trees grow in vigor, flowers hang evanescent, and mountains lie somnolent - with meaning. The promise of sculpture is to project these inner presences into forms that can be recognized as important and meaningful in themselves. Our heritage is now the world. Art for the first time may be said to have world consciousness."(Isamu Noguchi)93 Just like Noguchi, Greer relies on the relevance and force of the articulation of the material that he shapes. His art is about finding himself, a relocation in the world, a "making sense" of the world around him - thus finding the world in each of his sculptures and articulating that for others. Greer describes that with the sentence: "Making art is meeting God on a plain open field." (John Greer)94.

A very good example of Greer's search for essence is the work "Prehistory" 1995. Two "life-size" (measured against human size) figures carved from white Italian marble are lying on their back, supported by a galvanized steel stand. A slender woman figure with folded arms, reduced in her forms and with few surface detail, is reclining head to head with a much more solid bear. The bear's back is covered with line cuts and the front, the belly, is open, forming a gap that is showing rough stone, just wide enough to put the hand in it. The rough stone part is polished, and appears wet - in contrast to the smooth, but mat finish of the two figures.

These figures reference prehistoric artifacts. The woman is carved after a hand-size canonical figure from the Cycladic Islands in Greece, dated to the Keros-Syros culture and executed in marble in a height of 39cm/15 3/8". It was probably coloured in red ochre, since it bears traces of rubbed-in pigment.95 It is one of a variety of figures that were found in several graves, and once again, their meaning remains unknown. Even their original positioning, a point that is interesting in connection to Greer's "Prehistory", is vividly debated, since the toes are pointing downwards and might suggest a lying position, which is in opposition to an alternative standing or rather leaning of the figurine, that is currently favoured among archeologists.

The second figure is based on a "floating bear" from the Dorset Tradition found in the Igloolik region in Northern Canada close to the Arctic Ocean. It is 15,2cm/6” in length and made out of ivory.96

The bear was recorded fairly often in small sculpture of the Igloolik region, probably because of the strength and power that is connected to the Polar Bear and its man-like statue.

Greer is upscaling the small originals - and places the memory of two completely different cultures literally head to head. The figures do open a field of associations for the viewer, yet they are not figurative works, or even talking about death. They are transforming Greer's idea of a sculptural language, which is changing the awareness of time. The work is translating itself into the world of being. "I am not interested in replication. I think my work is trying to get a new look at the essence. Generally, talking about realists in terms of art, I think of them as replicators or somebody trying to do the perfection of an image, which I am not interested in. Or of virtuosity: If it is mere virtuosity, I think then it is a joke. It is like elegance is a joke if it is mere elegance. I try to be real, try to get it work." (John Greer)97. Here, the cultural objects gain importance through the reflection on the viewer as a cultural being.

In fact, the work is living out of its strong physical presence, an underlying physical attraction to engage with. Through the element of the unknown an aspect of transcendence is enclosed, which is enriching the encounter by creating a density and tenseness of experience.

When introducing the work, Greer is stressing the fact that you have to bend so far down in order to investigate the sculpture that you start to feel your own back. This is achieved by putting the figures on the steel support. Greer chose the lying position in order to express his concern for the stillness of the dialogue that he is creating. It is a stillness that is talking about the essence of life.

Using as much as is needed, with the least effort as possible solves the problem of the base. The positioning and scaling is essential in order to transfer an idea and at the same time to include the viewer as part of the work. This is done physically by the positioning on the floor, and through the reception of the work in terms of a cultural integration into the world.

The figures attract the touch of the hand, seem to be close and at the same time they are distant through the temperature and the purity of the surface of the material.

A space loaded with energy is created, coming to a peak between the two heads, which rest a hand width apart from each other. The figures enter an impressive dialogue, which leaves the viewer out. The reduced shapes recall in their resting position a transitional balance that is beyond of what we could verbally express.

Greer's sculptures arise questions that are reaching beyond culture and contemporary mutual understanding. In connection to the prehistoric Cycladic objects, Colin Renfrew writes: "Thus, when we find that these works of more than four thousand years ago seem to speak to us deeply about the human condition, we need not suppose that they provoked the same patterns of thought in the minds of their makers. Their "meaning" then, as it was consciously intended and perceived, may have been very much straightforward, practical and prosaic. What did those early sculptors care for the long span of human history? And what did they know of it?" (Colin Renfrew)98

Greer took those artifacts out of a timely narrative and made sculpture in stone, an affirmation that uses statements on various levels of understanding and approach in experience - and he is including the element of the unknown in order to translate the essence of meaning.

As cultural evidence from then to now, the bear and the woman relate to us with an energy of life - in the silence of rest.

87 Dennis Vialou in Frühzeit des Menschen, Verlag C.H. Beck

München, 1992, Universum der Kunst, Band 37; aus dem

Französischen übersetzt von Helga Weippert, p.14

88 Dennis Vialou, ibid., p.240

89 from Don E Dumond in The Eskimos and Aleuts, revised edition,

Thames and Hudson Ltd. London, 1977 pp.147.

90 from Colin Renfrew in The Cycladic Spirit,

Masterpieces from the Nicholas P. Goulandris Collection

Thames and Hudson Ltd, London 1991, pp.162.

91 John Greer in an interview with the author, march 1997 in Berlin

92 John Greer, ibid., referring to a statement in the catalogue "Black Seeds",

Glendon Gallery, Toronto 1997

93 Isamu Noguchi in Isamu Noguchi, a sculptor's world,

Thames and Hudson Ltd, London, 1967, p.40

94 John Greer in conversation with the author, Halifax, 1996

95 from Colin Renfrew in The Cycladic Spirit,

Masterpieces from the Nicholas P. Goulandris Collection

Thames and Hudson Ltd, London 1991, pp.78

96 from Don E Dumond in The Eskimos and Aleuts, revised edition,

Thames and Hudson Ltd. London, 1977 pp.98

97 John Greer in an interview with the author,

Berlin, March 1997

98 in Colin Renfrew in The Cycladic Spirit,

Masterpieces from the Nicholas P. Goulandris Collection

Thames and Hudson Ltd, London 1991, p.176